The illusion of mobility: why redistribution masks persistent gaps in skill formation

For to everyone who has will more be given, and he will have an abundance. But from the one who has not, even what he has will be taken away.

— Matthew 25:29

For decades, discussions on intergenerational mobility and equality of opportunity have celebrated the promise of redistributive policies. In particular, Scandinavian countries are often lauded as success stories where generous welfare states have effectively severed the link between parents' and children's economic outcomes. However, recent research challenges this narrative. A closer examination using data from Denmark reveals that its high intergenerational mobility rates may be largely an artifact of its tax and transfer systems rather than reflecting genuine equality of opportunity in skill formation. As a result, the underlying roots of inequality persist, raising questions about whether redistribution truly addresses the fundamental mechanisms through which advantages are transmitted across generations.

The Danish paradox

The Danish system offers a fascinating case study. Denmark has universal access to high-quality healthcare, free college tuition, equality in per-pupil educational expenditure across neighborhoods, universal pre-K education, generous childcare and maternity leave policies, and well-funded social security programs (Heckman and Landersø, 2022). At the same time, Denmark has one of the lowest levels of income inequality worldwide, while its intergenerational income mobility rates — the extent to which children's economic outcomes are independent of their parents' — rank among the highest. Such patterns are often attributed to the country's tax and transfers system, and are frequently cited as evidence that the American Dream of upward mobility is more alive in the Nordic countries than in the United States.

There are different ways to measure intergenerational mobility. Many studies have traditionally used the intergenerational income elasticity (IGE), which measures the correlation between parents' and children's income in a regression framework. Formally, this relationship can be expressed as:

$$ \log(y^{c}) = \alpha + \beta \log(y^{p}) + \epsilon $$

where $y^{c}$ is the child's income in adulthood, $y^{p}$ is the parent's income, and $\epsilon$ is an error term. The IGE is then given by the $\beta$ coefficient. A lower IGE indicates higher mobility, as children's outcomes are less dependent on their parents' income.1

The relationship between inequality and intergenerational mobility is perhaps best illustrated by what Alan Krueger dubbed the Great Gatsby Curve. Empirically, countries with higher income inequality (as measured by the Gini coefficient) tend to have lower intergenerational mobility rates (Figure 1). Denmark sits at one end of this curve, with low inequality and high mobility, while the United States occupies the opposite end. The intergenerational income elasticity in Denmark is around 0.15, compared to 0.5 in the United States, suggesting that parental income has a much smaller influence on children's economic outcomes in the Scandinavian country.2

Source: Corak (2013)

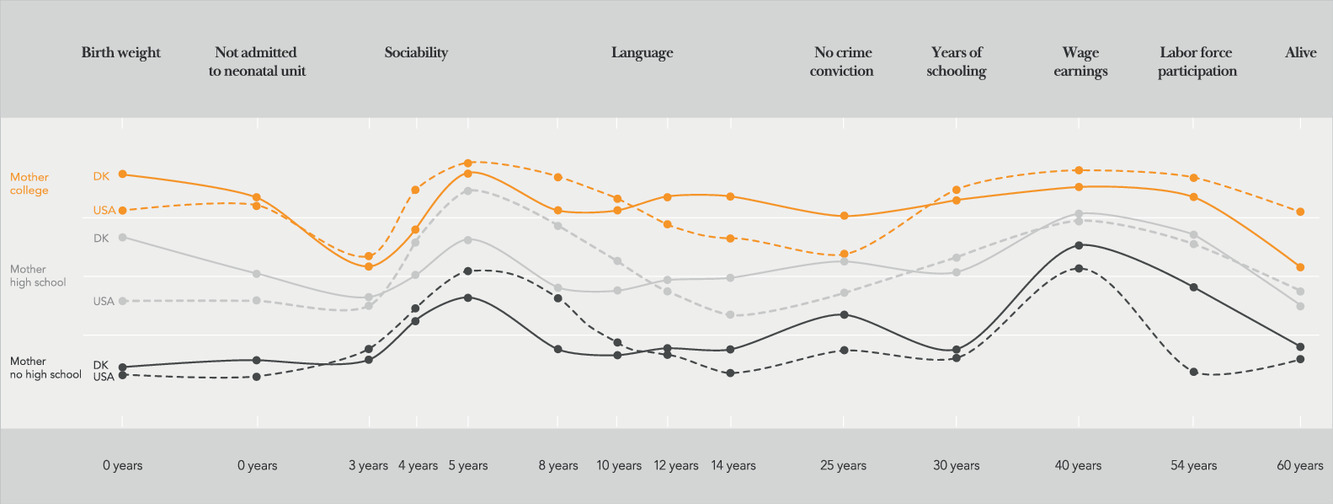

Yet beneath this veneer of success lies a surprising reality: family influence on many child outcomes in Denmark is remarkably similar to that observed in the United States (Figure 2). From birth weight and early childhood development metrics to educational attainment and labor market outcomes, children of college-educated mothers consistently outperform those whose mothers have less education. Indeed, analysis from large-scale administrative data from Denmark shows that its observed intergenerational mobility rates may be largely an artifact of its tax and transfer system rather than reflecting true equalization of economic opportunity and skill formation (Heckman and Landersø, 2017; 2022)

Studies typically calculate the IGE using post-tax income and thus factor in redistribution. However, when measuring mobility using pre-tax income (which reflects more accurately the returns to human capital and individual skills without the distortion of redistributive policies), Denmark's mobility rates mirror those found across the Atlantic. In other words, despite Denmark's generous redistributive policies, underlying skill formation and development processes remain almost as stratified by family background as they are in the much more unequal United States. This presents us with a paradox: how can a system that appears so successful at promoting equality show such persistent intergenerational dependencies in actual skills and capabilities?

Source: Heckman and Landersø (2022)

Family influence persists

Universal programs aim to level the playing field by providing equal access to public goods. However, even in the presence of such programs, families continue to exert significant influence on their children’s outcomes. In particular, more educated and affluent parents not only provide higher-quality time investments and educational support to their children, but they also prove more adept at navigating and capitalizing on resources provided by universal programs. This reflects what is often termed as the Matthew effect: the principle that to those who have, more is given.3

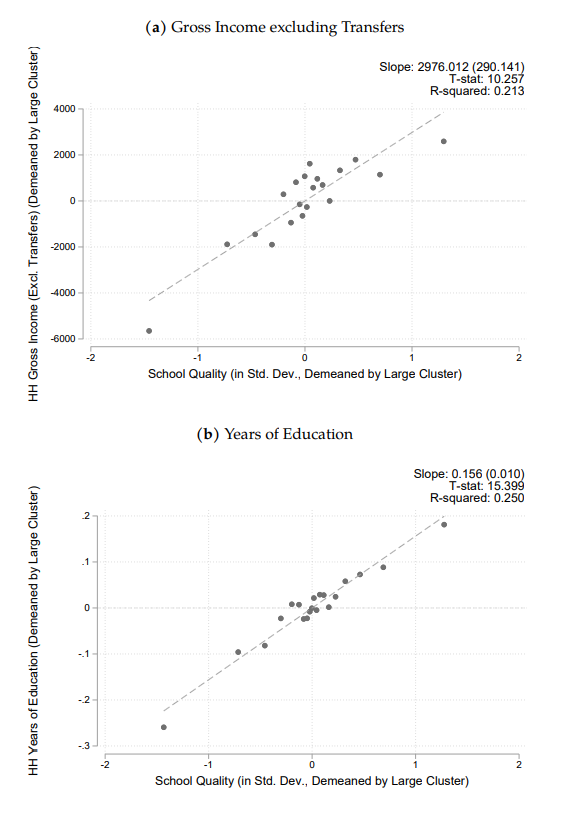

For example, more advantaged families make strategic choices about neighborhoods long before their children reach school age, clustering in areas with better schools and peer networks. Even with standardized teacher salaries across Danish schools, more advantaged areas tend to attract better teachers, creating de facto quality differences within the supposedly equal system. Figure 3 illustrates the relationship between individual characteristics of residents and school quality (measured by school-level average test scores and teacher qualifications) within narrowly defined neighborhoods in Denmark, showing that more affluent and educated families tend to sort into areas with higher-quality schools. The end result is that universal access does not translate into equality of opportunity — instead, advantaged families often extract disproportionate value from these programs, potentially even widening (rather than narrowing) gaps in skill formation.

Source: Eshaghnia et al. (2023)

Policy design matters

In the mid-20th century, Denmark employed more targeted approaches to social programs, focusing resources on the most disadvantaged groups rather than universalizing benefits. For instance, educational reforms in the 1950s specifically expanded access to secondary schooling in rural and working-class areas, while early childcare subsidies were initially means-tested based on family income. During this period, educational mobility increased substantially, with the intergenerational elasticity in education declining from around 0.5 to 0.3 for cohorts born between the 1940s and 1960s (Heckman and Landersø, 2022).

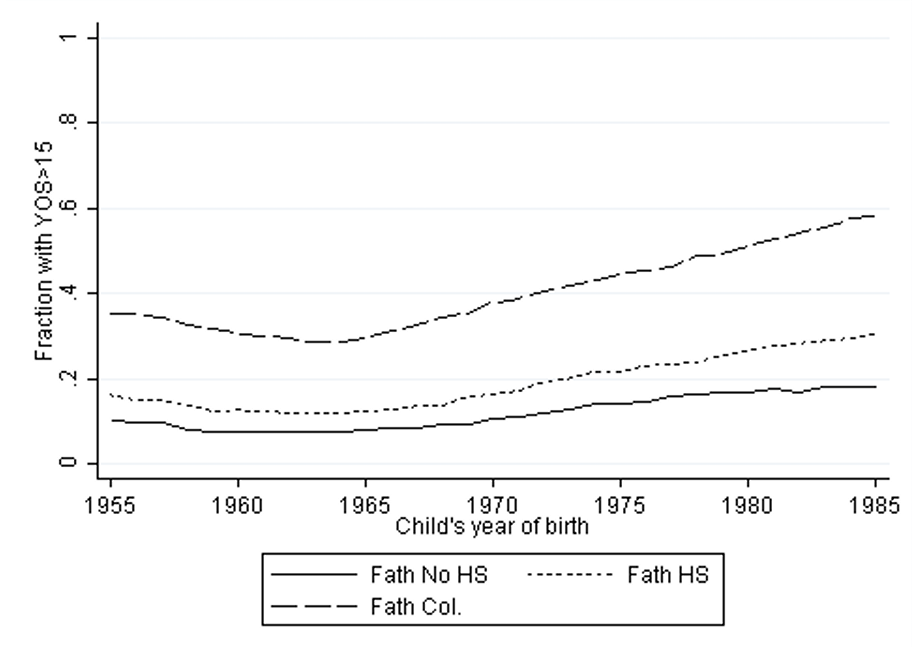

However, as Denmark shifted toward universal programs in the late 1960s and 1970s — including universal childcare access, standardized per-pupil school funding, and non-means-tested educational support — this progress began to stagnate. Free college tuition (first introduced in 1970 and substantially expanded in 1988) increased overall educational attainment, but did not seem to disproportionately benefit children from less-educated families. Among cohorts born in the 1960s, only 10% of children whose fathers had less than high school completed college, compared to 30% of children whose fathers had college degrees. By the 1985 cohort, after the universal policies were fully implemented, these rates had increased to 20% and 60% respectively (see Figure 4). The relative gap in college completion rates between children from different family backgrounds has thus remained unchanged.

Source: Heckman and Landersø (2017), Online Appendix (Figure A30e)

These findings point to a fundamental tension in policy design. While universal programs may be politically more palatable, they may inadvertently amplify advantages for already-privileged families through Matthew effects. In this context, policymakers might need to think more carefully about how to combine universal access with targeted support that specifically addresses skill formation in disadvantaged groups. Future policy initiatives along these lines might consider:

- Adopting a two-generation approach like the Nurse-Family Partnership Program, which provides targeted support for first-time mothers from low-income backgrounds. Such programs have shown success in improving both maternal and child outcomes (Heckman et al., 2017)

- Focusing on early childhood interventions (when skill gaps first emerge) modeled after successful programs. For instance, programs such as the Perry Preschool Project and the Abecedarian Project have shown long-term benefits in terms of educational attainment, employment, and health outcomes (Heckman et al., 2010; Campbell et al., 2014)

- Implementing other "smart targeting" mechanisms that identify and provide additional resources to disadvantaged families. This might include additional tutoring resources, enhanced family support services, or supplemental education programs for children identified as being at risk of falling behind

Beyond skill formation

While the evidence discussed above suggests important limitations of universal public service provision in promoting skill mobility, several policy considerations deserve attention. First, this analysis should not be interpreted as a broader critique of redistributive policies. Tax and transfer systems serve multiple welfare-enhancing functions beyond fostering intergenerational mobility, but discussing these lies outside the scope of this post.

Second, one could also argue that even with persistent skill gradients, lower intergenerational correlations in post-tax income still improve long-run welfare by accelerating regression to the mean across generations. In Denmark, for instance, the IGE estimate suggest that it would take fewer generations for disadvantaged families to reach middle-class status than in the US, potentially reducing the cumulative person-years spent in poverty across generations.4 Though this is all true, it does not follow that the underlying skill formation processes (which redistributive policies often fail to address) should be ignored. Steep skill gradients imply persistent misallocation of human capital development opportunities (and thus unrealized productive potential) in each generation, and therefore impose important efficiency costs on society.

A third consideration concerns the political economy of redistribution. While it may be more efficient to focus resources on the most disadvantaged groups, universal policies are often more politically appealing, enjoying greater public support and administrative simplicity (Korpi and Palme, 1998). Policymakers must balance the potential inefficiency of universal approaches against the risk that more narrowly targeted measures could face political resistance, stigma, or insufficient funding, which can ultimately leave some groups worse off.

Looking forward

The Danish experience offers a sobering lesson about the limitations of redistribution in creating genuine equality of opportunity. Even in a society with extensive universal programs and strong redistributive policies, family background continues to cast a long shadow over children's life trajectories. The illusion of mobility created by tax and transfer systems can mask persistent gaps in skill formation and perpetuate the intergenerational transmission of inequalities.

As we continue to debate mobility and inequality, we must ask ourselves: are we addressing the symptoms or the disease?

There are also other metrics to assess (relative) intergenerational mobility, such as rank-rank correlations and transition matrices, which have become more common in contemporary work.

There are different interpretations of the Great Gatsby Curve. The predominant causal explanation posits that higher inequality reduces intergenerational mobility through various mechanisms: credit constraints that limit human capital investment (Becker and Tomes, 1986), neighborhood effects and social externalities (Durlauf, 1996), and differential returns to educational investments across socioeconomic groups (Solon, 2004). However, the relationship can also be rationalized in the other direction: in steady-state models of intergenerational transmission, one can show that lower mobility mechanically generates higher cross-sectional inequality as advantages and disadvantages persist across generations (Corak, 2013).

The term Matthew effect was coined by sociologist Robert Merton in reference to the biblical verse "For to everyone who has will more be given, and he will have an abundance. But from the one who has not, even what he has will be taken away" in the Parable of the Talents (Matthew 25:29).

Put simply, lower post-tax IGE means that being born to poor parents has far less severe economic consequences in Denmark than in the US.

References

- Becker, G. S., & Tomes, N. (1986). Human Capital and the Rise and Fall of Families. Journal of Labor Economics, 4(3, Part 2), S1–S39.

- Campbell, F., Conti, G., Heckman, J. J., Moon, S. H., Pinto, R., Pungello, E., & Pan, Y. (2014). Early childhood investments substantially boost adult health. Science, 343(6178), 1478-1485.

- Corak, M. (2013). Income inequality, equality of opportunity, and intergenerational mobility. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 27(3), 79-102.

- Durlauf, S. N. (1996). A Theory of Persistent Income Inequality. Journal of Economic Growth, 1(1), 75–93.

- Eshaghnia, S. S. M., Heckman, J. J., & Razavi, G. (2023). Pricing neighborhoods. University of Chicago, Becker Friedman Institute for Economics Working Paper No. 2023-80. Retrieved from https://ssrn.com/abstract=4477536 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4477536

- Heckman, J. J., & Landersø, R. (2017). The Scandinavian Fantasy: The Sources of Intergenerational Mobility in Denmark and the US. Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 119(1), 178–230. https://doi.org/10.1111/sjoe.12219

- Heckman, J. J., & Landersø, R. (2022). Lessons for Americans from Denmark about inequality and social mobility. Labour Economics, 77, 101999.

- Heckman, J. J., Holland, M. L., Makino, K. K., Pinto, R., & Rosales-Rueda, M. (2017). An Analysis of the Memphis Nurse-Family Partnership Program. NBER Working Paper 23610.

- Heckman, J. J., Moon, S. H., Pinto, R., Savelyev, P. A., & Yavitz, A. (2010). The rate of return to the HighScope Perry Preschool Program. Journal of Public Economics, 94(1-2), 114-128.

- Korpi, W., & Palme, J. (1998). The paradox of redistribution and strategies of equality: Welfare state institutions, inequality, and poverty in the Western countries. American Sociological Review, 63(5), 661–687. https://doi.org/10.2307/2657333